Today’s Leadership Crisis Has a Clear (But Not Quick) Solution

A culture of apprenticeship is how businesses will rule the future

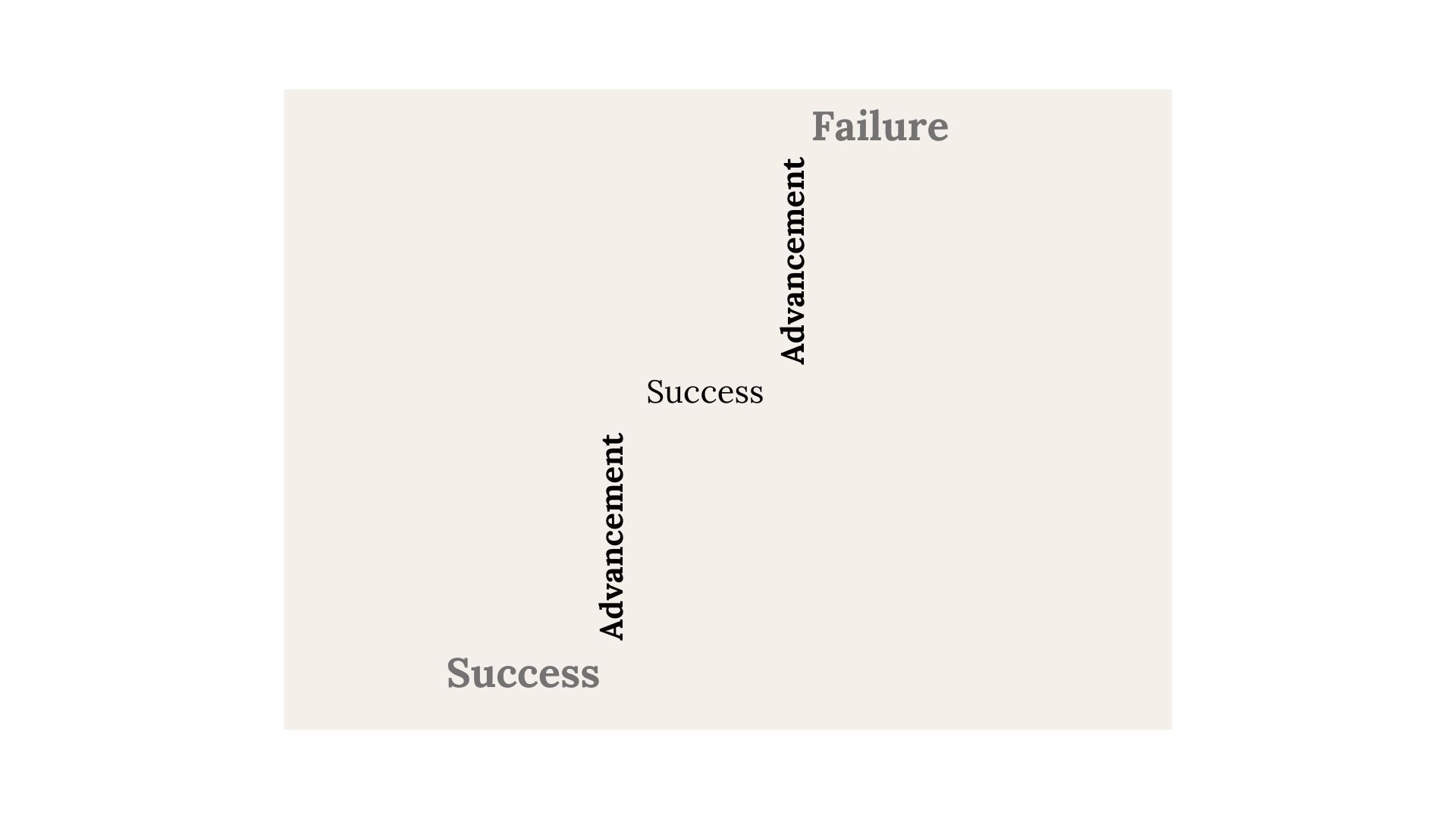

SUMMARY: There is a leadership crisis as a generation of leaders moves on without leaders ready to take their place. We tend to expect leaders to simply step up and prove themselves without offering any of the know-how and wisdom of those who’ve gone before them, resulting in fledging leadership running fledgling companies, and burning out in the process. Apprenticeship provides skills development for career advancement and a pipeline of those ready to lead into the future.

Imagine…

You get a great new job and you’re hitting it out of the park. The higher-ups are thrilled to promote you to a new role, one that’s wholly different than what you’ve been doing, but the salary bump cushions the pains that accompany experience gaps (at least a little).

Miraculously, you muster some big wins by calling in favors, though you barely know what you’re doing. You pull off another promotion to lead a big team, and even though it’s once again new territory, you figure you’ll fake it until you make it.

This time, you’re a round peg and the job is a square hole. Every time you show up to work, it’s like the lights are out; you try to feel your way but just keep bumping into things. Your bruises are impossible to conceal from those you lead and the higher-ups, who reckon you aren’t the shooting star you’d first appeared. Upward is no longer your trajectory. Having lived most of your life as a top performer, you’re eager to leave.

Imagine now instead you’re the boss of this company. You have an eye for talent and pushing people off the deep end to see if they can swim has proven an exhilarating strategy, as many paddle impressively, at least for a time. This tough-love approach seems to separate the good from the best. But as you look around, it seems most promising leaders have been promoted to a point where they stall—their weaknesses overshadow their strengths. You figure some have what it takes and some don’t. Too bad, you shrug. And yet you’re desperate for great leaders—the business is fledgling without them.

This is the Peter Principle lived out, which purports that so often people are promoted to their level of incompetence. Their current job performance is what’s considered for promotion over being fit and ready for the future role. Done at scale, this runs companies into the ground.

And yet, this happens all the time. The superstar salesperson is now attempting to manage the sales team, without any team management know-how. The brilliant software coder is now the CIO, unable to decode the bureaucracies she’s now tasked to navigate. The top-rated professor is now a top administrator, even though his primary skills are in the classroom.

None of this means people shouldn’t be promoted. It means there’s a glaring omission in how they make the transition from one role to the other.

The Case for Apprenticeship

If offered the process of apprenticeship, most people who are willing to learn and grow (those carrying the key quality of curiosity) can prepare well for higher callings of leadership. Alternately, apprenticeship can also help people discover early if a path is not right for them before officially stepping into a role that’s messy to get out of.

While attendance is surging in apprentice-based trade schools, apprenticeship is a rare practice within business environments, officially present in 1% of the labor market (incidentally, the NBC / BBC show The Apprentice was a sink-or-swim model with no actual apprenticeship included or awarded—any misstep meant “you’re fired,” quite the opposite of the grace-filled training true apprenticeship supplies).

The Peter Principle is becoming all the more problematic within the present crisis of leadership—the “silver tsunami,” as it’s being called, is on our doorstep, where a generation of Baby Boomer leaders are retiring after serving as the core of the workforce for the past 40 years, without a pipeline of leaders to carry the torch after them. (And these tenured leaders are taking their knowledge and experience with them—57% of still-working boomers say they’ve passed along less than half the knowledge essential to succeed in their roles, despite being overwhelmingly willing to do so.)

Deloitte’s Global Human Capital Trends report reveals most executives feel their companies are not prepared to meet their leadership needs. DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast states only 11% of HR leaders say they have a “strong bench” to fill leadership positions, the lowest number in a decade.

We recently chatted with a successful businessman; newly 70, he and his business partner are eager to pass over the reins of the company they built together. But there’s no one to pass it off to. They have a team of great people, but he said the heir apparent doesn’t have the right skill set, and the others don’t have the experience or connections necessary.

They’re stuck. Do they shut the company down at a loss? Do they attempt to sell it? Do they take a big risk on someone not ready?

When asked if anyone within the company had been mentored to be ready to take on the top role, a quizzical look answered and revealed the all-too-common “they either have it or they don’t” perspective. After 50 years of business success, he may have no choice but for his equity and legacy to dwindle.

The pandemic deepened the leadership crisis, as so many companies shifted their efforts to survival over succession planning and leadership development, while simultaneously many would-be leaders jumped ship in search of better opportunities.

According to the NeuroLeadership Institute, “The result is a ‘lost generation’ of leaders—employees promoted into leadership who received far less feedback, assessment, and mentoring.”

It’s clear many companies (most, even) have an impending leadership dilemma, and it’s also clear aspiring leaders long to be developed:

● 40% will leave their job within one year due to lack of development and training

● 94% won’t quit if they’re offered opportunities to be developed

● When employees receive leadership training, their performance increases by 20%

● 63% of Millennials believe they aren’t being developed as leaders by their superiors

● Job growth and learning opportunities are more important to leaders than job security, job fulfillment, and flexible schedules.

Apprenticeship is the solution to both problems.

Barriers to Implementing Apprenticeship Programs

The Information Age combined with Individualism can prevent us from seeing apprenticeship as a wise pathway. Amidst the world of online everything, people are more apt to type questions into a machine than ask humans who carry hard-fought lessons of experience. We’re endlessly wooed by the persona of a rare, talent-filled genius, and we hope, just like Trinity in The Matrix, that the moment we’re asked to fly a helicopter, we’ll simply download all that experiential knowledge from some chip and be ready for takeoff.

This hope afflicts potential apprentices and mentors alike. Though the fallacy is obvious, we lead as if those in our stead can—and should—just figure it out.

But imagine life before the internet. Better yet, imagine life before books. How did one learn anything at all? Through mentors, the oldest form of education. It was everyone’s responsibility to pass knowledge and skills to the next generation.

From medieval craftsmen to Renaissance artists, this pay-it-forward tradition ensured skills, secrets, and techniques were preserved through generations; blending the ‘how’ of a technician with the ‘why’ of an artist. Even when classrooms and schooling became a norm, it was understood that the only way to learn a craft, trade, or philosophy with a level of mastery was to live it alongside the person who’d been doing it longer and better than you have, to fastidiously shadow, ask questions, and be given more and more hands-on practice and responsibility as you were ready.

Standing on the shoulders of giants is how humanity progressed into the modern era—the era in which we tend to believe mentorship isn’t necessary when we have supercomputers in our pockets.

Another barrier: a culture of apprenticeship sounds great in a perfect world, but what calendar-harried leader has time for it?

Let’s get practical.

In Karl Martin’s new book, The Cave, The Road, The Table and The Fire, he offers this wisdom:

I’ll bet a gut reaction as you read it is that your leadership life is too busy for this. But this is the vital work of your leadership life. So, you can’t afford not to do this.

Don’t dazzle from a distance, but give [apprentices] a little room to get their hands dirty alongside you. Open your schedule to them. You don’t need to add a huge number of extra meetings, just cheat a little.

If I’m traveling, I may as well travel with someone and give them a role. As I prepare a keynote, I might as well ask for help with a portion. To release a new generation of leaders, you don’t have to become busier, but you may need to invite others to help, even where you don’t need it.

The Apprenticeship Square Model for Leadership Development

The model we use with our clients at Arable is called the four-step Apprenticeship Square.

[We tried to find out who authored this model, but it has been iterated on by many. An early apprenticeship model was provided by David Ausubel in his book Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View (1968) and the model was developed further by Allan Collins, John Seely Brown, and Ann Holum in their book Cognitive Apprenticeship: Making Thinking Visible (1989). The Cognitive Apprenticeship Research Laboratory at Northwestern University has progressed this as well. Giant Worldwide uses a version credited to A. Maslow, Gordon Training International.]It's a journey that requires a mutual inclination towards curiosity, where learning is active and immersive. From observing and assisting to leading then teaching, the square encapsulates evolving from learner to leader.

From Karl’s book, ‘The Cave, The Road, The Table, and The Fire’:

I do, you watch

Your team, at this stage, is unconsciously incompetent. But you’re not! They need to hear you work out what you do and how you do it. So intentionally pull them in close, invite them into conversations they should observe, have them eat lunch with you while you think through an issue at hand out loud. They need your stories, your perspectives, your voice. Generously give room for their curious questions.

I do, you help

This is where the observers who’ve become learners are invited to be participants. [As noted above, take things you’re already doing, and give team members a role. Ask for help in projects where you might not even need it–or think strategically where you do, and give team members a chance to add value.]

You do, I help

They are in the driver’s seat, although you can get a hand on the wheel, if necessary. This process, if practised properly, is going to irritate you. It slows you down. You’ll want to just do it yourself. But younger leaders will need to fail and make a mess on your watch, with your reputation on the line and with your relational and leadership capital exposed and vulnerable. You’ll have some messes to clear up. But that’s what it takes to lead with soul.

You do, I watch

This is when the leader becomes a fan. Your team’s experience is becoming unconscious competence. You may have no functional leadership role, but you’re leading from a distance, there to advise when asked.

This model challenges leaders to integrate teaching into their leadership style, ensuring knowledge is not just shared, not just retained, but also passed on, creating a legacy of wisdom and growth. Apprenticeship is a great benefit to leaders too–it enriches our own understanding and ensures that our wisdom doesn't just age but evolves.

Essentials for Incorporating Apprenticeship in Your Culture

Be patient:

The timeline for this process will vary. Don’t rush it. Don’t cut corners. Getting to a place where you have a continuous stream of leaders ready to step into new roles and responsibilities will take years.

Be intentional:

Look for every opportunity to teach and empower, even if it slows you down. You’ll need to remember that leadership isn’t simply caught—it must be taught. A sink-or-swim strategy only brings to light the ethics of being willing to let people sink on your watch.

Be curious:

Most importantly, a spirit of curiosity is needed from all parties involved. Leaders need to be curious about how far others may be able to go; curious about the introverts, the unproven, and those who don’t fit your stereotype of “leader.” Leaders must eschew the tunnel vision of task completion, instead asking curious questions to facilitate learning and exploration. Mentees must be open to opportunities they might not naturally be open to, to vigorously ask questions to illuminate all sides of the subject matter.

The positive outcomes of apprenticeship are vast. Product quality, reputation preservation, sustained wisdom, and a trajectory of consistent business growth more than prove the ROI of this strategy–those are all the byproducts of a culture where individuals come to work each day with confidence and satisfaction. Seek to empower your people, and they will power your product.

Let’s no longer allow it to be commonplace for people to leap while everyone holds their breath (including the leaper), but instead, provide a natural progression toward deserved promotion through apprenticeship.